Teaching languages: the role of the European Union and the Member States

In the European Union (EU) more than 500 million Europeans come from diverse ethnic, cultural and linguistic backgrounds and it is now more important than ever that citizens have the skills necessary to understand and communicate with their neighbours. All European citizens should be able to communicate in at least two languages other than their mother tongue. The Council of Europe promotes plurilingualism in response to European linguistic and cultural diversity. It then sets out some criteria to be satisfied.

In accordance with the ‘principle of subsidiarity’ each EU Member State is fully responsible for organising its educational systems as well as the content of the programmes.

The Union’s role in this field is not to replace action by Member States, but to support and supplement it. To do this, the EU has put in place numerous actions designed to promote language education and learning under the framework of Community programmes, particularly in the areas of education, culture, the audiovisual sector, and the media.

The European Survey on Language Competences (ESLC) is a collaborative effort among the 16 EU major participating educational systems and SurveyLang partners to measure the language proficiency of approximately 54,000 students across Europe. These conclusions called for ‘action to improve the mastery of basic skills, in particular by teaching at least two foreign languages from a very early age’ and also for the ‘establishment of a linguistic competence indicator’ (European Commission 2005). Each educational system tested students in two languages the most widely taught of the five most widely taught official languages of the EU: English, French, German, Italian and Spanish. This effectively meant that there were two separate samples within each educational system, one for the first test language, and one for the second. Each sampled student was therefore tested in one language only. The ESLC sets out to assess students’ ability to use language purposefully, in order to understand spoken or written texts, or to express themselves in writing. Their observed language proficiency is described in terms of the levels of the Common European Framework of Reference (Council of Europe 2001), to enable comparison across participating educational systems. The data collected by the ESLC will allow participating educational systems to be aware of their students’ relative strengths and weaknesses across the tested language skills, and to share good practice with other participating educational systems.

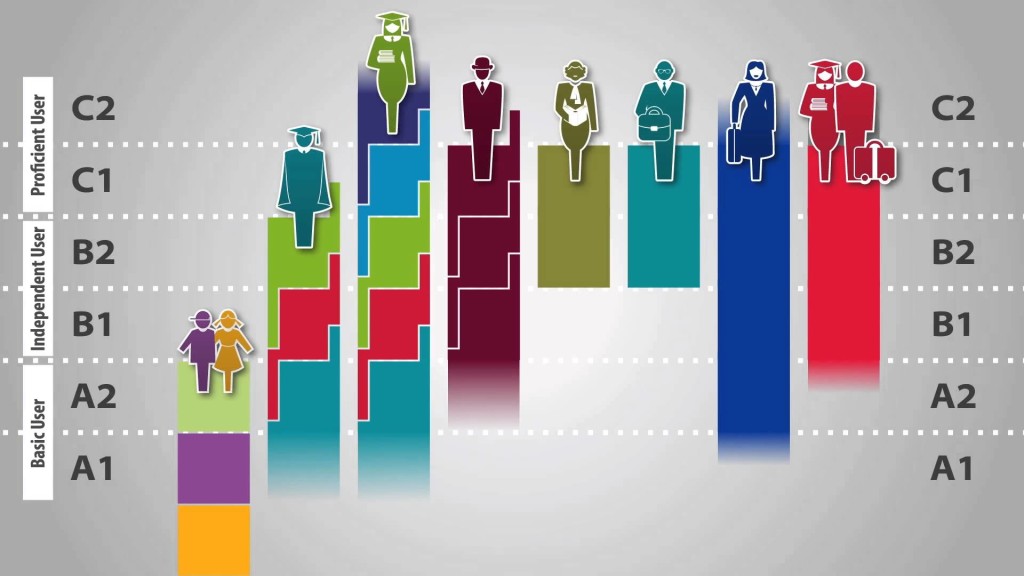

The language tests covered three language skills: Listening, Reading and Writing in five test languages: English, French, German, Italian and Spanish. Each student was assessed in two out of these three skills in one test language and also completed a contextual questionnaire. Students were tested at one of three overlapping levels on the basis of a routing test. The language tests measure achievement of levels A1 to B2 of the Common European Framework of Reference (CEFR) (Council of Europe, 2001).

The European Framework provides a common basis for the elaboration of language syllabuses, curriculum guidelines, examinations, textbooks, etc. across Europe. It describes in a comprehensive way what language learners have to learn to do in order to use a language for communication and what knowledge and skills they have to develop so as to be able to act effectively. The description also covers the cultural context in which language is set. The Framework also defines levels of proficiency which allow learners’ progress to be measured at each stage of learning and on a life-long basis.

The Common European Framework is intended to overcome the barriers to communication among professionals working in the field of modern languages arising from the different educational systems in Europe. It provides the means for educational administrators, course designers, teachers, teacher trainers, examining bodies, etc., to reflect on their current practice, with a view to situating and co-ordinating their efforts and to ensuring that they meet the real needs of the learners for whom they are responsible. By providing a common basis for the explicit description of objectives, content and methods, the Framework will enhance the transparency of courses, syllabuses and qualifications, thus promoting international co-operation in the field of modern languages. The provision of objective criteria for describing language proficiency will facilitate the mutual recognition of qualifications gained in different learning contexts, and accordingly will aid European mobility. The taxonomic nature of the Framework inevitably means trying to handle the great complexity of human language by breaking language competence down into separate components. This confronts us with psychological and pedagogical problems of some depth. Communication calls upon the whole human being. The competences separated and classified below interact in complex ways in the development of each unique human personality. As a social agent, each individual forms relationships with a widening cluster of overlapping social groups, which together define identity. In an intercultural approach, it is a central objective of language education to promote the favourable development of the learner’s whole personality and sense of identity in response to the enriching experience of otherness in language and culture. It must be left to teachers and the learners themselves to reintegrate the many parts into a healthily developing whole. The Framework includes the description of ‘partial’ qualifications, appropriate when only a more restricted knowledge of a language is required (e.g. for understanding rather than speaking), or when a limited amount of time is available for the learning of a third or fourth language and more useful results can perhaps be attained by aiming 1 at, say, recognition rather than recall skills. Giving formal recognition to such abilities will help to promote plurilingualism through the learning of a wider variety of European languages.